Recovering deleted files from Valve VPKs

When I’m reversing a complicated target like a video game, I commonly keep a “Find in Files”-dialog pointed at the target’s root directory handy as a means of quickly getting an idea of how things are related to each other by searching for specific strings or magic values. Of course this can go wrong in many ways (compression, encryption, string hashes, just to name a few), but quite often it’s a very fast and convenient way to get a good overview.

When I was searching for a particular pattern in this way while working with Half-Life: Alyx, I found a number of matches in .vpk files, which is Valve’s custom archive format for Source Engine (Valve PaK). Every .vpk can contain a number of files, so in order to narrow down which files contained the pattern, I unpacked the archive. The format is well-documented and lots of tools exist to unpack it, so this is easy enough.

However, peculiarly, searching the unpacked files yields fewer matches than searching the packed .vpks, which I found very confusing. If anything I’d have expected more matches in the unpacked files than in the archives, as some matches might’ve been obscured by compression or some other encoding. What’s going on?

The VPK file format

Let’s have a look at what these files look like to get a better idea of what we’re working with. I’ll skip over details not relevant to the discussion, you can consult the documentation if you’re interested.

An individual VPK ‘package’ is split over several .vpk files. There’s a single directory VPK (e.g. pak01_dir.vpk) and a number of content VPKs, which are numbered (e.g. pak01_024.vpk).

The directory VPK is effectively just a list of entries for each file consisting of path, content VPK number, offset and size for each. It’s a bit more elaborately encoded (to save a bit of space they get grouped by type and path) but that doesn’t really make a difference for our purposes.

The content VPKs are just flat binary files where the contents are stuffed into one after another.

All in all, the format is very simple, providing no apparent reason for these extra matches. Even more confusingly, the additional matches are all in the content VPKs, not the directory. Given the content VPKs are supposed to consist of nothing more than padding and the data in the contained files, what could possibly be happening?

What’s happening?

To figure out what files these extra matches are supposed to be contained in, we can go through every entry in the directory VPK and check if a match is contained in the data referenced by that entry– we just check that the content VPK index matches and that it’s in the referenced range. By this we should be able to get file paths and offsets for all matches, which we can then look at. A couple of lines of Python later however, the answer is: they aren’t contained in files at all. For some matches, there’s simply no entry that references that section of data. It’s just there.

At this point I had enough of the insanity and decided to take a look at the tool Valve uses to build VPK files. Fortunately Valve tend to be very open about shipping their developer tools with Source engine games, and indeed Half-Life: Alyx is no exception. vpk.exe -? shares some insights:

VPK - Pack File Tool ( Build: May 27 2020 )

Copyright (c) Valve Corporation, All rights reserved.

Usage: vpk [options] <command> <command arguments ...>

vpk [options] <directory>

vpk [options] <vpkfile>

[...]

Options:

[...]

-max_total_slack_kb <size> (In kilobytes)

-max_total_slack_pct <pct> (0--100)

Max allowed slack space across all chunks for SteamPipe-friendly builder.

Slack space is created when a file is deleted or updated, and the old

version of the file not removed in an incremental build. Utilizing

slack space can be desirable to limit the number of VPKs that are

touched, since SteamPipe will rewrite the entire chunk. If an

absolute size and percentage are specified, whichever limit is effectively

LARGER will apply. Approx 3x the chunk size is the minimum amount needed

for the builder to reorder files over time. If file order is not important,

then a smaller value can be used, but a minimum of one chunk is recommended.

The default is 3%

[...]

That “slack space” sounds very much like the unreferenced data we identified earlier, and the usage info also answers the “why”: if you need to update a file stored in a big content VPK, Steam’s update system apparently either doesn’t have the capability to just update that section (potentially changing its size), this is just suboptimal in terms of disk I/O, or something else entirely. I’m not sure which. Whatever the problem, slack space is Valve’s solution: you can simply leave the old data in the content VPK, add the new contents (if any) into a new content VPK and rewrite the directory VPK to point at the new copy. This way, the old content VPK doesn’t have to be changed at all, only the directory VPK and new data needs to be written to disk.

So at last the solution to our initial mystery: those spurious matches we found are old copies of files which have since gotten updated or deleted, but have been left in their respective content VPKs.

This presents us with a possibility which, out of context, sounds rather ridiculous, at least to me: we can recover deleted files from VPK files.

Recovering deleted files

First, we read through the directory VPK, and for every file we track where it’s located by content VPK, offset and size. After we’ve accounted for every file, we simply look for any big gaps in the content VPKs where no files are stored. This is a bit fiddly because vpk.exe inserts padding between subsequent files, but we can assume that everything big that doesn’t consist of just zeros is a deleted or overwritten version of a file. Finally, we can simply dump these to disk for inspection.

And this actually works! Running it against the current version of Half-Life: Alyx recovers a number of old versions of files from the various updates to the game. But here’s where it gets interesting: what if we run this against the launch day version of Half-Life: Alyx?

As it turns out, there’s a few files we can recover from before the game was shipped. Unfortunately this turns out to be largely uninteresting since Valve accidentally left the prerelease version available for download from Steam for a while, so most of the things we can recover were already available. Notably, we can recover some text files which were present in the prerelease but are entirely missing in the launch day version, so this technique is not just applicable to overwritten files, but deleted ones too. But mostly it’s not particularly interesting in the case of Half-Life: Alyx; boring changes to material parameters and stuff like that.

Additionally, there’s a few limitations to all this:

- There is an upper limit to how much slack space is allowed when updating a VPK, so in most cases we can’t recover every single previous version of every file.

- We don’t have file paths available for what we recover, so it’s largely down to guessing by contents. A lot of Source 2 asset files contain strong clues about their path as part of their metadata, which helps a lot.

- When two files that are adjacent to each other in a content VPK are simultaneously deleted/overwritten, they will end up as one unaccounted for region, and it’s not entirely clear where (or whether) we need to split it to get back individual files. Again, Source 2’s asset format helps a lot here, since most files start with a 4-byte size field giving the exact size of the file, however some files like textures have trailing data which is not included in this size, and some files just don’t have this field. As such it’s non-trivial to automatically split these regions into the right files without being able to parse all the file formats. There is existing tooling which actually can parse a lot of them, so integrating with this could potentially give much better splitting than my crude heuristics. For now, the result of a region that isn’t properly split is that when opening it in a viewer, you only see the first file, and the second file remains hidden.

- This obviously only works on VPKs which actually use this slack space feature.

- When a VPK is created from scratch, like it appears Valve does when they release a game, the slack space feature is not used, and so there’s nothing left for us to recover, save for small updates made just before launch. This is likely why we can’t recover that much from the launch day version of Half-Life: Alyx.

Those last two in combination have the consequence that for most games I’ve checked, we can’t recover much of interest from before launch. With one notable exception.

Aperture: Desk Job

Recently Valve has begun shipping the Steam Deck, and along with it has released a companion game running on Source 2 called “Aperture: Desk Job”, and this game’s VPKs utilize the slack space feature. Most importantly however, it appears that Valve didn’t rebuild the VPK from scratch prior to release. As a result, we can recover more than 170 versions of files from before the game’s release. A lot of these are older versions of files that shipped with only minor changes, however there’s also early development versions of some files which offer insights into Valve’s development process (which is a fancy way of saying they’re cool to look at). There’s too much here to go through one by one, but here’s a couple of fun examples.

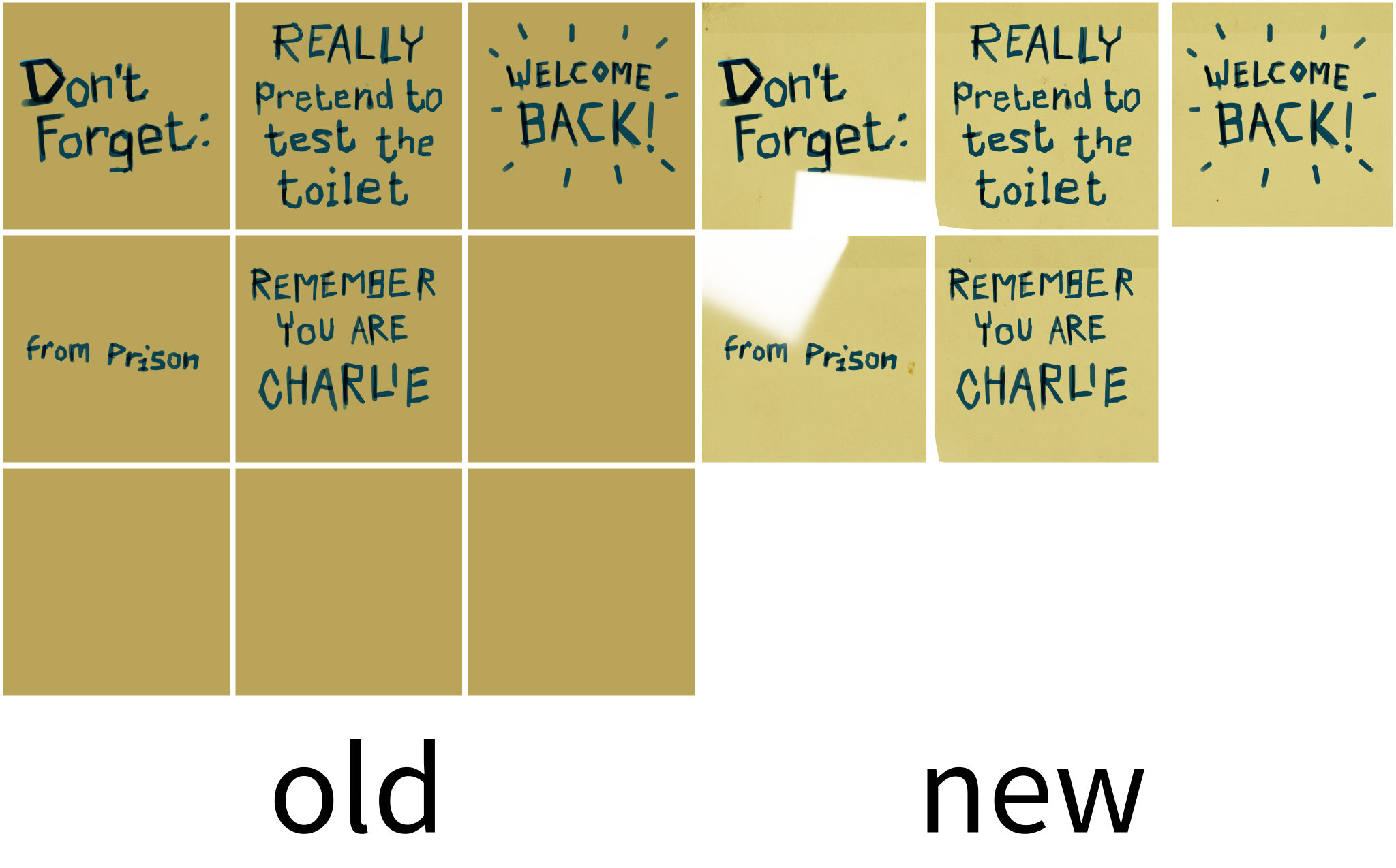

These sticky notes were first designed intact, and then weathered after:

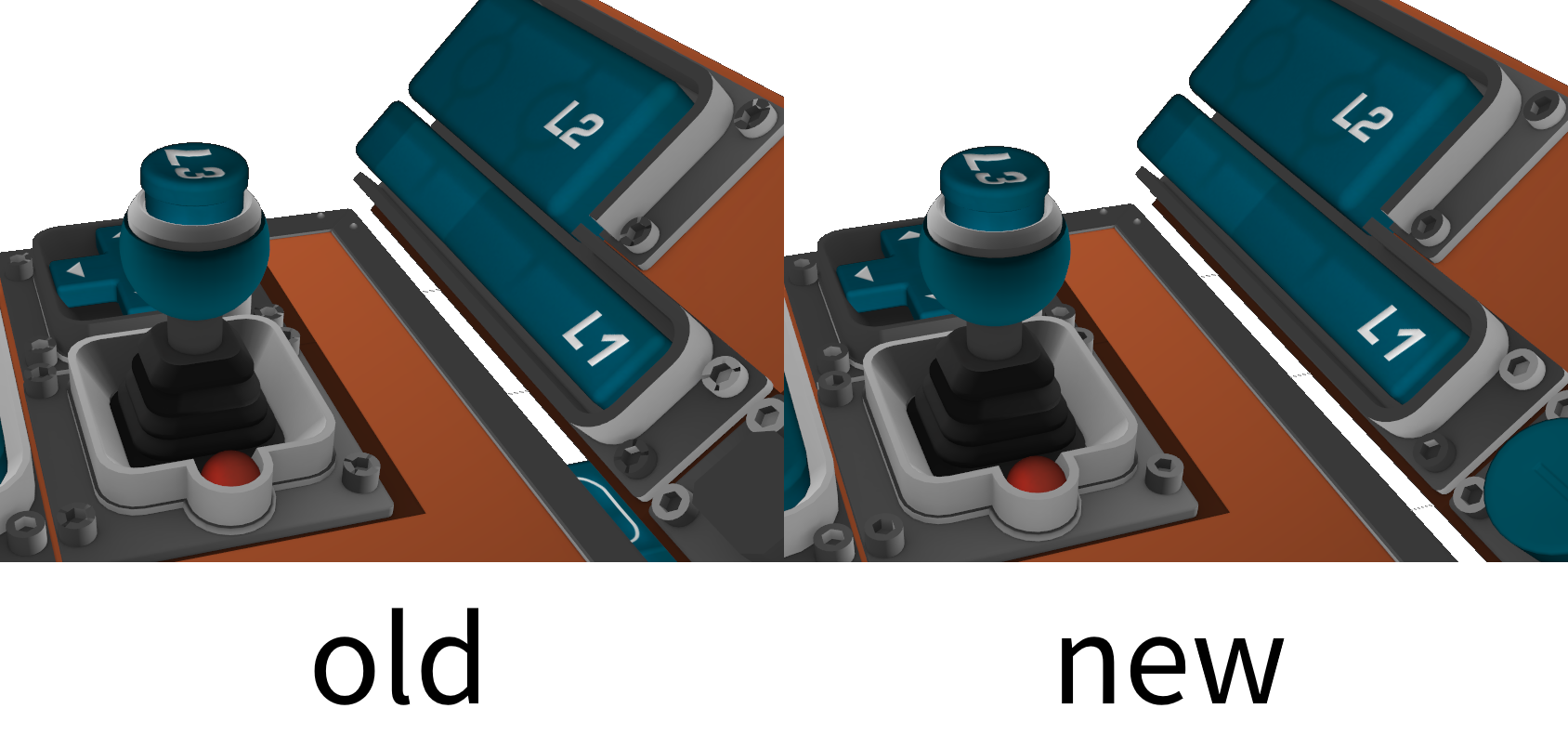

On the model of the main desk, the screws were swapped from cross to hex drive:

Lua scripts for the game are also shipped within the VPKs, so we can observe code changes to those as well. For example, here’s where they changed the name of the game:

--- aperture_desk_job_V0.lua

+++ aperture_desk_job_V1.lua

@@ -132,7 +132,7 @@

-----------------------------------------------------------

function SteamPalPrint( msg )

msg = msg or ""

- print( "STEAMDECK DEMO: " .. msg )

+ print( "DESK JOB: " .. msg )

end

Conclusion

Half-Life: Alyx and Aperture: Desk Job are the games I’ve looked at the most for recovering data, but other Source 2 titles like Artifact Foundry and Dota Underlords both appear to have recoverable files in their launch day versions. It’s possible that there are some hidden gems to find there.

So far we’ve looked basically solely at the launch day versions of games because they basically guarantee that anything we recover will be pre-launch and thus interesting. However, depending on how Valve ships updates, it doesn’t seem entirely implausible that there could also be interesting files recoverable from updates, beyond the ones which are visibly deleted and overwritten. If for example during development of a larger update (that changed multiple files) a file was added, the VPK rebuilt, the file removed and the VPK again rebuilt, could that file possibly now exist in slack space and could thus be recoverable from the shipped update? I’m not sure.

I’ve published my Python script to perform the recovery process here. There’s also a standalone version available here. Simply run it in the directory with the VPKs you want to recover files from and it’ll create a folder with everything that’s been dumped. I used VRF for the screenshots demonstrating the differences of the recovered files to the shipped ones.

And that’s it for now. If you recover something interesting using this technique, let me know on Twitter!